“Yes, right now I am hungry, almost hangry. Hangry is hungry and angry,” says Arthur Vandendaele, a 9-year-old whose favorite food is chicken nuggets served with curry ketchup. “So, you get too hungry, and you get mad and sad.”

Arthur is just one of thousands of kids experiencing food insecurity this summer in Harvesters’ service area. With school out of session and no access to free breakfast and lunch meals at school, families turn to Harvesters’ network of food pantries and to summer meal programs like the one at the YMCA North for help.

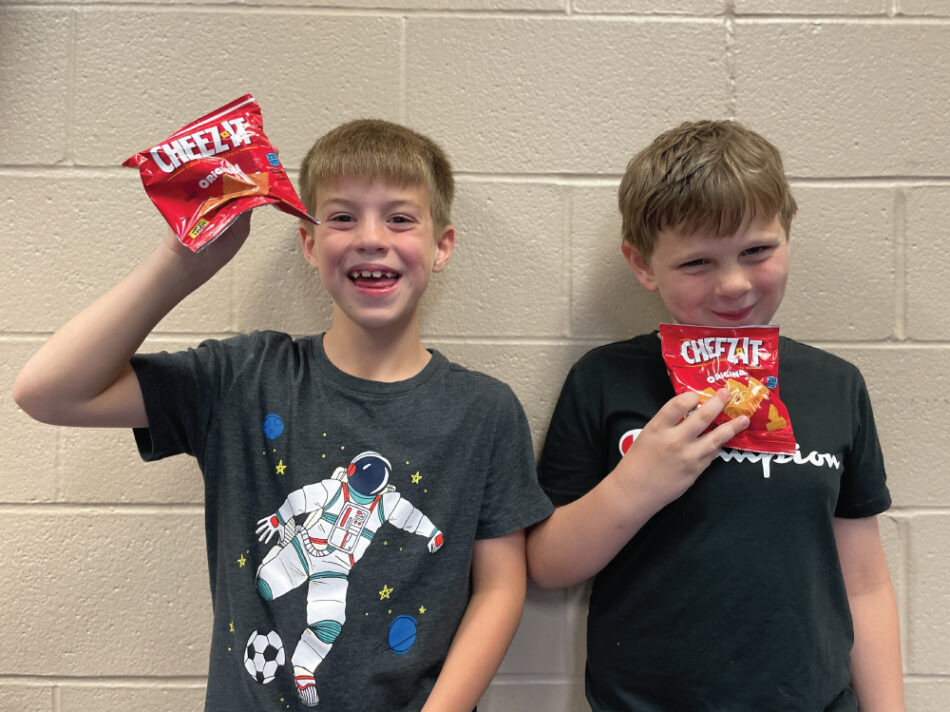

Although the 7, 8 and 9-year-olds attending the summer program are unaware of the role Harvesters plays in providing sack lunches and snacks through the summer feeding program, they do understand what it feels like to be hungry.

“If I didn’t eat breakfast, I’ll be super hungry (for lunch), but if I ate breakfast, I’ll be hungry, but not super hungry,”” says 7-year-old Benjamin Stead, whose favorite food is mac and cheese.

Asked what it feels like to be hungry, Jack Glaves, whose favorite food is Nutella, uses the same word as Arthur, “hangry.”

When he’s asked: “Does your tummy rumble?”

“A lot! Like right now,” he answers.

Cornel Tang sees firsthand how hard it is for kids and teens to concentrate and behave when they don’t have enough to eat.

“When I started my position, I used to have snacks in my office. I’d get all these snacks at the store, and I’d think they’d last me a whole month, but they’d last like five hours. (Kids) are growing, and they’re always hungry, but some of them just don’t have food at home,” says Tang, who was a defensive coordinator for the Kansas City Panthers before he took the role of Best Buy Teen Tech Center Coordinator at the YMCA.

Tang was on the verge of creating his own feeding program when he heard about Harvesters’ resources and reached out for help. He’s since added a Harvesters mobile distribution to the YMCA calendar of events.

“There’s a big need, not just with the kids, but with the adults also. We’re seeing an increase of not just this neighborhood, but we’re also seeing people coming from different cities,” Tang says. ““I think people are more comfortable coming out and asking if they need help, where it was taboo for them to even ask for it before the pandemic. Now it’s out there, and there are all these food resources, such as churches, schools and community centers with pantries.”

If there was one thing Tang would like to add to his outreach efforts, he sees a need for hot meals.

“Thank you, Harvesters, for being a source. Someone has to do it, and it makes it easier for those of us who want to do something about food insecurity,” Tang says.